by crissly | Mar 6, 2024 | Uncategorized

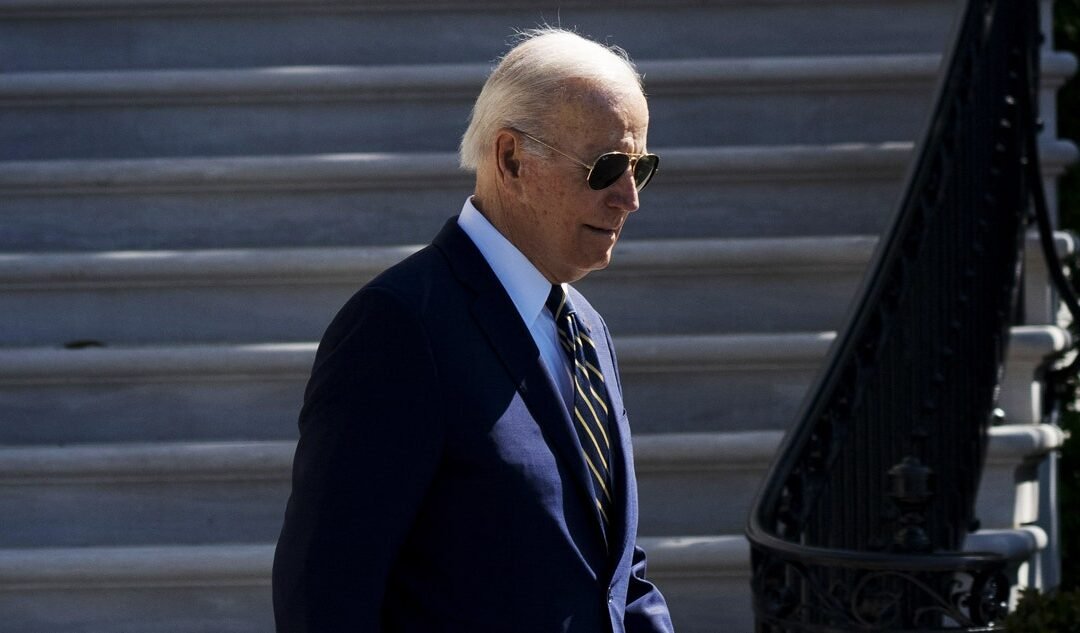

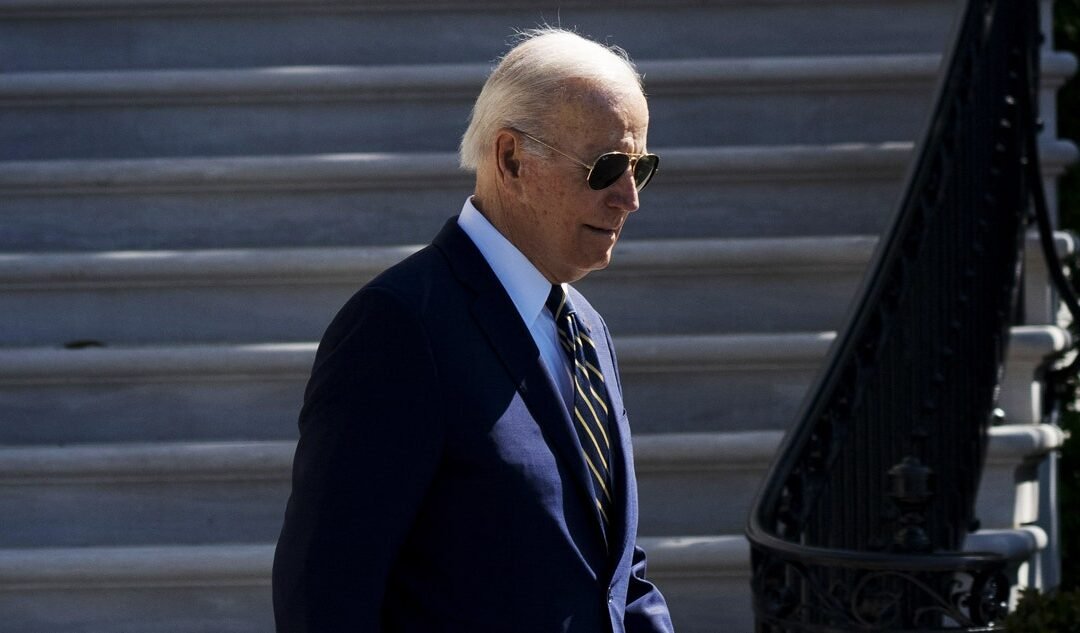

San Francisco made history in 2019 when its Board of Supervisors voted to ban city agencies including the police department from using face recognition. About two dozen other US cities have since followed suit. But on Tuesday, San Francisco voters appeared to turn against the idea of restricting police technology, backing a ballot proposition that will make it easier for city police to deploy drones and other surveillance tools.

Proposition E passed with 60 percent of the vote and was backed by San Francisco mayor London Breed. It gives the San Francisco Police Department new freedom to install public security cameras and deploy drones without oversight from the city’s Police Commission or Board of Supervisors. It also loosens a requirement that SFPD get clearance from the Board of Supervisors before adopting new surveillance technology, allowing approval to be sought any time within the first year.

Matt Cagle, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, says those changes leave the existing ban on face recognition in place but loosen other important protections. “We’re concerned that Proposition E will result in people in San Francisco being subject to unproven and dangerous technology,” he says. “This is a cynical attempt by powerful interests to exploit fears about crime and shift more power to the police.”

Mayor Breed and other backers have positioned it as an answer to concern about crime in San Francisco. Crime figures have broadly declined, but fentanyl has recently driven an increase in overdose deaths, and commercial downtown neighborhoods are still struggling with pandemic-driven office and retail vacancies. The proposition was also supported by groups associated with the tech industry, including the campaign group GrowSF, which did not respond to a request for comment.

“By supporting the work of our police officers, expanding our use of technology, and getting officers out from behind their desks and onto our streets, we will continue in our mission to make San Francisco a safer city,” Mayor Breed said in a statement on the proposition passing. She noted that 2023 saw the lowest crime rates in a decade in the city—except for a pandemic blip in 2020—with rates of property crime and violent crime continuing to decline further in 2024.

Proposition E also gives police more freedom to pursue suspects in car chases and reduces paperwork obligations, including when officers resort to use of force.

Caitlin Seeley George, managing director and campaign director for Fight for the Future, a nonprofit that has long campaigned against the use of face recognition, calls the proposition “a blow to the hard-fought reforms that San Francisco has championed in recent years to rein in surveillance.”

“By expanding police use of surveillance technology, while simultaneously reducing oversight and transparency, it undermines peoples’ rights and will create scenarios where people are at greater risk of harm,” George says.

Although Cagle of the ACLU shares her concerns that San Francisco citizens will be less safe, he says the city should retain its reputation for having catalyzed a US-wide pushback against surveillance. San Francisco’s 2019 ban on face recognition was followed by about two dozen other cities, many of which also added new oversight mechanisms for police surveillance.

by crissly | Sep 6, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tech companies and privacy activists are claiming victory after an eleventh-hour concession by the British government in a long-running battle over end-to-end encryption.

The so-called “spy clause” in the UK’s Online Safety Bill, which experts argued would have made end-to-end encryption all but impossible in the country, will no longer be enforced after the government admitted the technology to securely scan encrypted messages for signs of child sexual abuse material, or CSAM, without compromising users’ privacy, doesn’t yet exist. Secure messaging services, including WhatsApp and Signal, had threatened to pull out of the UK if the bill was passed.

“It’s absolutely a victory,” says Meredith Whittaker, president of the Signal Foundation, which operates the Signal messaging service. Whittaker has been a staunch opponent of the bill, and has been meeting with activists and lobbying for the legislation to be changed. “It commits to not using broken tech or broken techniques to undermine end-to-end encryption.”

The UK’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport did not respond to a request for comment.

The UK government hadn’t specified the technology that platforms should use to identify CSAM being sent on encrypted services, but the most commonly-cited solution was something called client-side scanning. On services that use end-to-end encryption, only the sender and recipient of a message can see its content; even the service provider can’t access the unencrypted data.

Client-side scanning would mean examining the content of the message before it was sent—that is, on the user’s device—and comparing it to a database of CSAM held on a server somewhere else. That, according to Alan Woodward, a visiting professor in cybersecurity at the University of Surrey, amounts to “government-sanctioned spyware scanning your images and possibly your [texts].”

In December, Apple shelved its plans to build client-side scanning technology for iCloud, later saying that it couldn’t make the system work without infringing on its users’ privacy.

Opponents of the bill say that putting backdoors into people’s devices to search for CSAM images would almost certainly pave the way for wider surveillance by governments. “You make mass surveillance become almost an inevitability by putting [these tools] in their hands,” Woodward says. “There will always be some ‘exceptional circumstances’ that [security forces] think of that warrants them searching for something else.”

Although the UK government has said that it now won’t force unproven technology on tech companies, and that it essentially won’t use the powers under the bill, the controversial clauses remain within the legislation, which is still likely to pass into law. “It’s not gone away, but it’s a step in the right direction,” Woodward says.

James Baker, campaign manager for the Open Rights Group, a nonprofit that has campaigned against the law’s passage, says that the continued existence of the powers within the law means encryption-breaking surveillance could still be introduced in the future. “It would be better if these powers were completely removed from the bill,” he adds.

But some are less positive about the apparent volte-face. “Nothing has changed,” says Matthew Hodgson, CEO of UK-based Element, which supplies end-to-end encrypted messaging to militaries and governments. “It’s only what’s actually written in the bill that matters. Scanning is fundamentally incompatible with end-to-end encrypted messaging apps. Scanning bypasses the encryption in order to scan, exposing your messages to attackers. So all ‘until it’s technically feasible’ means is opening the door to scanning in future rather than scanning today. It’s not a change, it’s kicking the can down the road.”

Whittaker acknowledges that “it’s not enough” that the law simply won’t be aggressively enforced. “But it’s major. We can recognize a win without claiming that this is the final victory,” she says.

The implications of the British government backing down, even partially, will reverberate far beyond the UK, Whittaker says. Security services around the world have been pushing for measures to weaken end-to-end encryption, and there is a similar battle going on in Europe over CSAM, where the European Union commissioner in charge of home affairs, Ylva Johannson, has been pushing similar, unproven technologies.

“It’s huge in terms of arresting the type of permissive international precedent that this would set,” Whittaker says. “The UK was the first jurisdiction to be pushing this kind of mass surveillance. It stops that momentum. And that’s huge for the world.”

by crissly | Mar 9, 2023 | Uncategorized

“Nobody’s defending CSAM,” says Barbora Bukovská, senior director for law and policy at Article 19, a digital rights group. “But the bill has the chance to violate privacy and legislate wild surveillance of private communication. How can that be conducive to democracy?”

The UK Home Office, the government department that is overseeing the bill’s development, did not supply an attributable response to a request for comment.

Children’s charities in the UK say that it’s disingenuous to portray the debate around the bill’s CSAM provisions as a black-and-white choice between privacy and safety. The technical challenges posed by the bill are not insurmountable, they say, and forcing the world’s biggest tech companies to invest in solutions makes it more likely the problems will be solved.

“Experts have demonstrated that it’s possible to tackle child abuse material and grooming in end-to-end encrypted environments,” says Richard Collard, associate head of child safety online policy at the British children’s charity NSPCC, pointing to a July paper published by two senior technical directors at GCHQ, the UK’s cyber intelligence agency, as an example.

Companies have started selling off-the-shelf products that claim the same. In February, London-based SafeToNet launched its SafeToWatch product that, it says, can identify and block child abuse material from ever being uploaded to messengers like WhatsApp. “It sits at device level, so it’s not affected by encryption,” says the company’s chief operating officer, Tom Farrell, who compares it to the autofocus feature in a phone camera. “Autofocus doesn’t allow you to take your image until it’s in focus. This wouldn’t allow you to take it before it proved that it was safe.”

WhatsApp’s Cathcart called for private messaging to be excluded entirely from the Online Safety Bill. He says that his platform is already reporting more CSAM to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) than Apple, Google, Microsoft, Twitter and TikTok combined.

Supporters of the bill disagree. “There’s a problem with child abuse in end-to-end encrypted environments,” says Michael Tunks, head of policy and public affairs at the British nonprofit Internet Watch Foundation, which has license to search the internet for CSAM.

WhatsApp might be doing better than some other platforms at reporting CSAM, but it doesn’t compare favorably with other Meta services that are not encrypted. Although Instagram and WhatsApp have the same number of users worldwide according to data platform Statista, Instagram made 3 million reports versus WhatsApp’s 1.3 million, the NCMEC says.

“The bill does not seek to undermine end-to-end encryption in any way,” says Tunks, who supports the bill in its current form, believing it puts the onus on companies to tackle the internet’s child abuse problem. “The online safety bill is very clear that scanning is specifically about CSAM and also terrorism,” he adds. “The government has been pretty clear they are not seeking to repurpose this for anything else.”

by crissly | Jan 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tens of thousands of people have been laid off at Amazon, Meta, Salesforce and other once-voracious tech employers in recent months. But one group of workers has been particularly shortchanged: US immigrants holding H-1B visas for workers with specialist skills.

Those much-sought visas are awarded to immigrants sponsored by an employer to come to the US, and the limited supply is used heavily by large tech companies. But if a worker is laid off, they have to secure sponsorship from another company within 60 days or leave the country.

That’s a particularly tough situation when the larger companies that sponsor most tech-related visas are also those making layoffs and freezing hiring. Amazon and Meta, which together have announced at least 29,000 layoffs in recent months, each applied to sponsor more than 1,000 new H-1B visas in the 2022 fiscal year, US Citizenship and Immigration Services figures show.

US dominance in science and technology has long depended on a steady flow of talented people from overseas. But the H-1B system—and US immigration as a whole—hasn’t evolved much since the last major immigration bill in 1986. Now, pandemic-era economic uncertainty is reshaping tech giants and shining a new spotlight on the system’s limitations. It shows workers, companies, and perhaps the US as a whole losing out.

“Because our system has been so backlogged, these visa holders have built lives here for years, they have a home, and children, and personal and professional networks that extend for years,” says Linda Moore, president and CEO of TechNet, an industry lobbying group that includes nearly all of the major tech companies. “They’ve just been stuck in this system that gives them no clarity or certainty.”

Over the past decade, tech companies that are typically fierce competitors have been in unusually strong lockstep on the question of H-1B immigration. They apply for lots of the visas, want the annual supply of 85,000 increased, and have lobbied for changes to the application process that would make it easier for high-skilled workers to stay in the US for good. An H-1B visa holder can generally only stay for six years unless their employer sponsors them to become a permanent US resident, or green card holder.

That was the path taken by Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, who is rarely outspoken on political issues but has been vocal about his personal support for immigration reform. He has argued that both his personal success and the success of his company depended upon the high-skill immigration system.

Tech workers outside the US appear to love H-1Bs, too, despite the system’s limitations. The visas provide a way for ambitious coders to get closer to the epicenter of the global tech industry, or to leverage their skills into a fresh start in the US.

Nearly 70 percent of the visas went to “computer-related” jobs in the 2021 fiscal year, according to data from US Citizenship and Immigration Services, and many of these workers eventually convert their visas into permanent US residency. But because of restrictions on the number of employment-based residency applications granted each year, it can take decades for immigrants from larger countries like India to receive a green card, leaving many people working on an H-1B tied to one employer for years. During that time they are vulnerable to life-disrupting shocks like those facing some immigrants caught up in the recent tech layoffs.

by crissly | May 17, 2022 | Uncategorized

The US announced today that it will fund data-gathering on the conflict in Ukraine. In addition to laying the groundwork for war-crime prosecutions, the move would share critical, real-time data with humanitarian organizations.

The newly established Conflict Observatory will use open source investigation techniques and satellite imagery to monitor the conflict in Ukraine and collect evidence of possible war crimes. Outside organizations and international investigators would be able access the resulting database, a US State Department spokesperson confirmed in an email.

Partners for the Conflict Observatory include Yale University’s Humanitarian Research Lab, the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, artificial intelligence company PlanetScape Ai, and Esri, a geographic information systems company, according to a State Department press release. The Observatory will have access to commercial satellite data and imagery from the US government, which will “allow civil society groups to move at a faster pace, towards a speed once reserved for US intelligence,” says Nathaniel Raymond, a lecturer at Yale’s Jackson School of Global Affairs and a coleader of the Humanitarian Research Lab.

Raymond himself is no stranger to using technology to investigate conflicts and crises. More than a decade ago he was the director of operations for the Satellite Sentinel Project, cofounded by actor George Clooney, which used satellite imagery to monitor the conflict in South Sudan and documented human rights abuses. It was the first initiative of its kind but would be too costly and resource-intensive for other organizations to replicate.

“This kind of work is very labor-intensive,” says Alexa Koenig, executive director at the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley School of Law. “I think on the money and capacity side, we’re at a moment where a lot of these organizations do need to be thinking about the information environment in which they’re working. Open source information can be invaluable at the preliminary investigation stage, as you’re planning either humanitarian relief or to conduct a legal investigation.”

None of the data the Observatory will use and disseminate is classified; the satellite imagery will be taken from the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s commercial contracts with private companies. But having access to many types of data in one place, rather than spread across many different entities, and the ability to analyze it, would make it powerful. Although the Observatory would be using publicly available data, it does not plan to make its data open source, unlike many other humanitarian projects, according to Raymond.

“The level of detail and how fast, in some cases, imagery data can be collected means that it could have value for those seeking to target civilians and protected infrastructure like hospitals and shelters,” he says.

Raymond is particularly aware of these kinds of risks. While he was at Satellite Sentinel, a report that the group published may have led to the kidnapping of a group of Chinese road workers by the South Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Though the image had been de-identified by removing longitude and latitude, Raymond says locals could have recognized the terrain and identified where the road crew was.